Know Before You Go: Critical Dam Awareness on Waterways

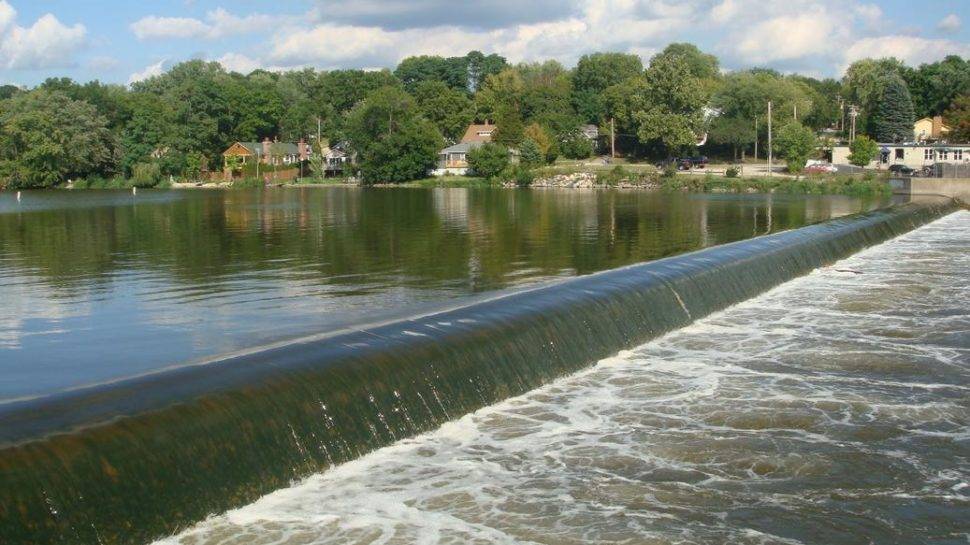

Low-head dams don’t look particularly menacing. Thousands of these low-level structures were built on American rivers and streams in the 1800s and early 1900s to power gristmills and small industries.

With a short drop of up to 5 feet, low-head dams can seem like a minor inconvenience-or even a thrill-for paddlers and swimmers. However, the churning waters at the base of these dams present a high level of danger to the unwary.

Since 1960, more than 350 fatalities have occurred at low-head dams in the United States, according to Dr. Bruce Tschantz, professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee and a low-head dam expert. Two-thirds of these fatalities occurred in the past 15 years, and most occurred on weekends between April and August.

Dangers

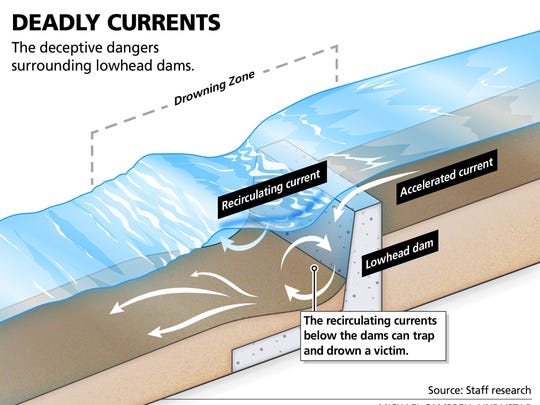

Often referred to as ”drowning machines,” low-head dams produce dangerous recirculating currents, large hydraulic forces, low buoyancy and other hazardous conditions sufficient to trap and drown victims.

Upon entering the churning water at the base of the dam, the victim is pounded by a never-ending wave of water that forces them to the bottom. If they can bob up to the surface, the recirculating current carries them back to the dam and the nightmare begins again.

In 153 incidents where 335 people were known to go over a low-head dam, 68 percent either drowned or were injured, according to Tschantz’s research. Even life vests become ineffective because the foamy, turbulent water is highly aerated and has very little buoyancy for humans, he said.

“Even Olympic swimmers wouldn’t be able to overcome these forces & currents”

Low-head dam numbers: Unknown

There are no reliable inventories of how many exist in the U.S. today, but a study by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates there may be as many as 5,000 low-head dams across the country.

There are three known low-head dams on waterways in this area: on the Sequatchie River at Ketner’s Mill in Whitwell, Tennessee; on South Chickamauga Creek in Graysville, Georgia; and at the confluence of Oostanaula Creek and the Hiwassee River in Calhoun, Tennessee.

In July 2015, three men drowned on the Sequatchie River at Ketner’s Mill. Two brothers were swimming in the river when one was swept over the low-head dam. The other brother and another man jumped into the water to save him, but police said all three drowned. A near-drowning occurred there the day before, as well.

Dam regulations, removal

In Tennessee, dams less than 6 feet, regardless of impoundment volume, or dams impounding less than 15 acre-feet are not regulated for safety.

“Dam removal is an excellent way to remove the public safety risk, improve recreational opportunities and improve the health of a river,” Erin Singer McCombs, associate director of Southeast conservation with American Rivers.

Sixty-one dams have been removed across Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina, according to McCombs. Removals in Tennessee include Brown’s Mill Dam on the Stones River near Murfreesboro and Richland Creek Dam and Sevenmile Creek Dam in the Nashville area.

Dam awareness

Public safety experts urge all swimmers, anglers, boaters, paddlers and tubers to check river maps and ask locals for locations of dangerous structures before setting out on any unknown waterway.

Avoid approaching low-head dams and all spillway structures from both upstream and downstream, especially during high-water conditions.

Watch for a smooth horizon line where the stream meets the sky, which can potentially indicate a dam.

To learn more, watch the low-head dam safety video produced by the Illinois Paddling Council and visit www.SafeDam.com.

Jenni Veal